The Subtle Charm of Art: Arte Povera in Paris

One of the major exhibitions of this Autumn has just opened in Paris — Arte Povera at the Bourse de Commerce. François Pinault's collection showcases the Italian avant-garde movement known as «poor art», tracing its origins from the 1960s to the present day. The exhibition not only highlights the artistic movement itself but also presents it within the broader context of the era that shaped it.

Essentially, this exhibition is an encyclopedia of this post-war social phenomenon, which emerged in Italy and is certainly more than just an artistic movement. To fully experience all the floors and galleries, you’ll need to spend a few hours. The exhibition’s curator, renowned art historian and former director of the Castello di Rivoli Museum, Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, has been exploring the movement form since the 1980s and curating exhibitions dedicated to it in various cities around the world from New York to Moscow, and now, Paris. This time, Christov-Bakargiev carefully selected works for the one-of-a-kind retrospective, including 50 pieces from François Pinault’s personal collection. Pinault is an avid fan and has been passionately gathering Arte Povera works all his life, so it’s no wonder, that the quality of these works is both exceptional and representative. Overall, Christov-Bakargiev selected more than 250 masterpieces, adding emblematic works from other private and public collections.

The term Arte Povera was invented in 1967 by critic Germano Celant, and the art movement itself emerged as a social phenomenon, a counterpoint to the dominant pop art of the time. Seen as an aesthetic revolution, akin to André Breton’s surrealist manifesto, Arte Povera draws from everyday materials, ordinary objects, and simple constructions that, in the hands of these artists, challenge conventional notions of art and its materials. It is also symbolic that three major art movements — Surrealism at the Centre Pompidou, Pop Art at the Fondation Louis Vuitton, and now Arte Povera at the Bourse de Commerce — are simultaneously on display in Paris.

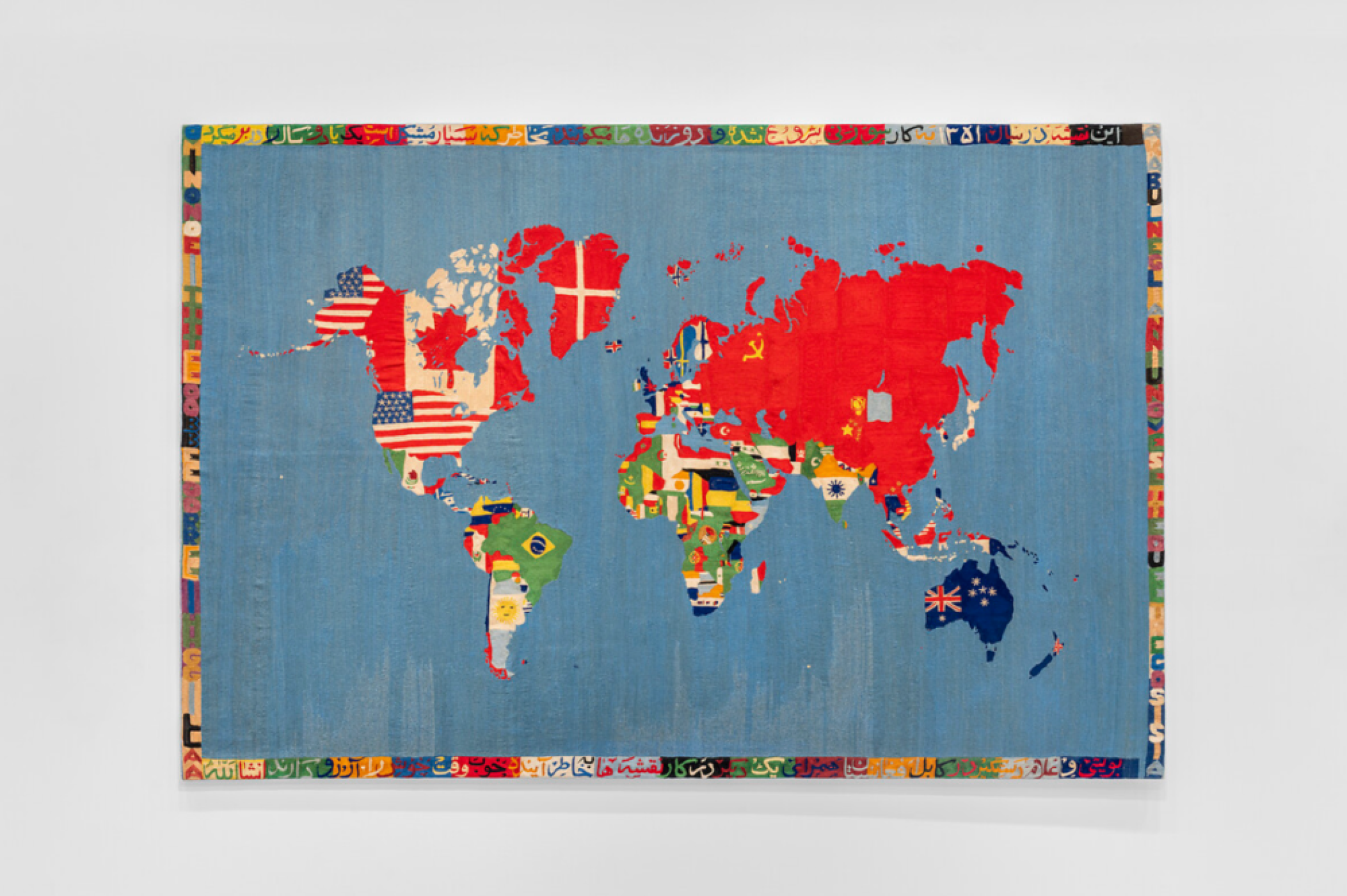

The crème de la crème of this «poor art» is luxuriously displayed in the Rotunda, which once served as a trading hall — a setting that itself hints at the post-ironic sensibility of these Italian conceptualists. For the first time, the museum’s prime space in the centre of Tadao Ando’s cylinder is dedicated to a group exhibition featuring 13 leading artists united by a shared aesthetic vision - a nod to their very first collective exhibitions in Turin and Rome. Each presents its own emblematic object. Gilberto Zorio’s hideous black stain or large rubber blot suspended from the ceiling looms over other significant works from that era — Pino Pascali’s army-green machine gun pointed at viewers, Luciano Fabro’s unconscious marble body under a white cloth, Michelangelo Pistoletto’s symphony of kettles, Marisa Merz’s high-heeled shoes made of copper wire, Mario Merz’s very long white neon tube emerging from bundles of straw, Alighiero Boetti’s bronze self-portrait with his hand steaming hot air and Giulio Paolini’s two Venuses hovering above them.

A level higher in the gallery, another «rag Venus» by the veteran and most famous ambassador of the movement, Michelangelo Pistoletto, steps down from her pedestal to bury her nose into a pile of secondhand clothes, elevating them and bringing them back to life, colliding worlds of inspiration and consumption. Pistoletto, in his earlier works, invited viewers to become co-authors of the performance by placing an enormous mirror in front of them, as in a dressing room, so their reflection, alongside classical sculptures and paintings, would immediately become part of the creative act. This goes beyond a mere selfie with filters.

At the heart of the Rotunda, Alighiero Boetti’s highly playful Smoking Fountain—a full-length self-portrait statue with a water jet cooling a smoking brain. Perhaps this is, indeed, a metaphor for the fountain of ideas in this poor, but poetic art. Mario Merz builds shamanistic igloos out of glass and branches as well as Fibonacci sequences of neon numbers and restaurant photographs, creating something both cult-like and mystical. He does this much like Gilberto Zorio, an alchemist who conducts his chemical experiments with metals, electric light, and liquids in the museum’s basement. Each artist’s universe and retrospective demands hours of contemplation, as each one crafts something that shouts about the complexity of our existence using the simplest materials: Marisa Merz works with kitchen utensils, Jannis Kounellis with proletarian coal, white wool, or even live horses, while Giuseppe Penone creates from wood and used mattresses.

Courtesy: Bourse

de Commerce

Text: Editorial team