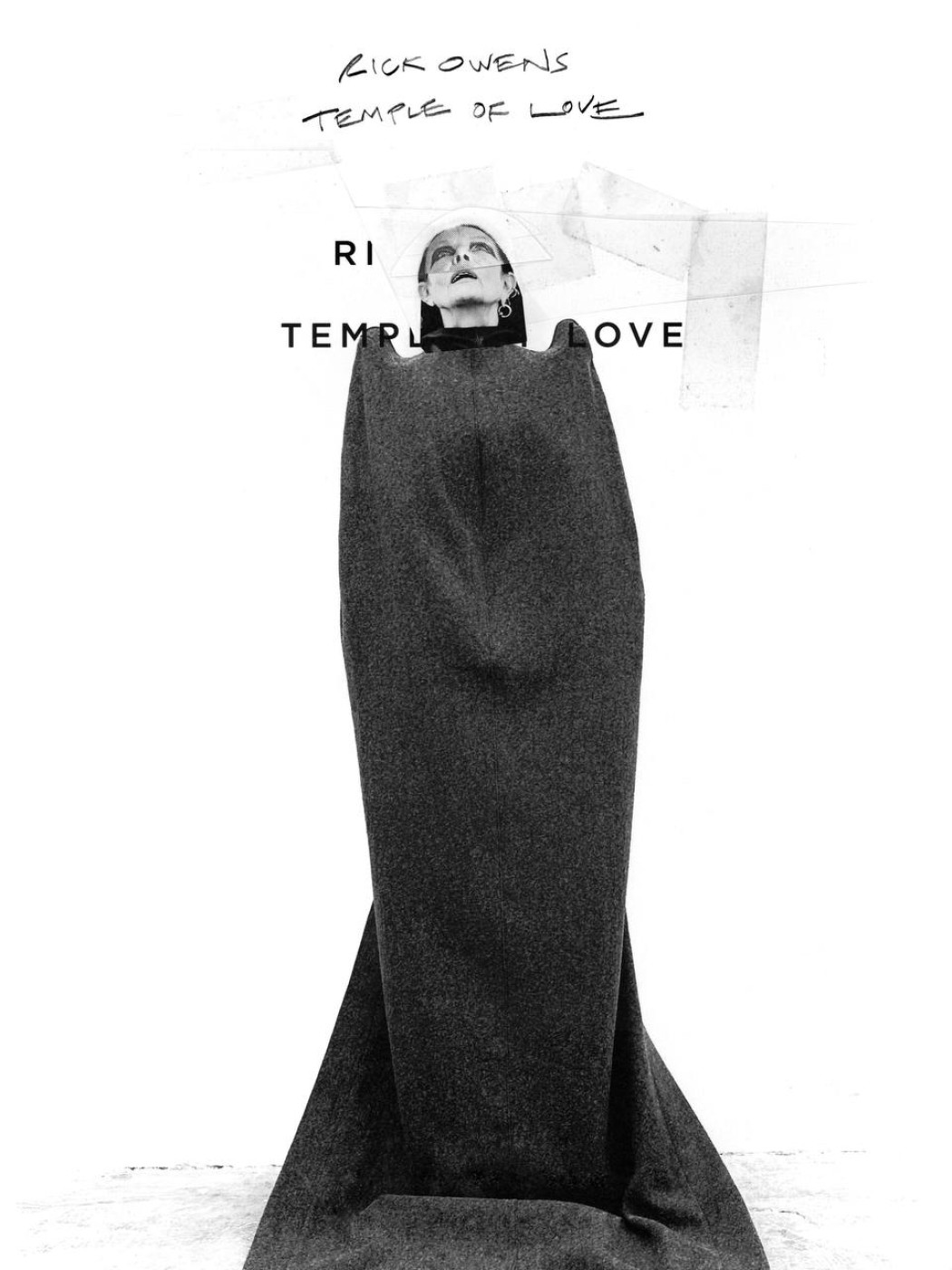

Inside Temple of Love: Palais Galliera’s Monumental Tribute to Rick Owens

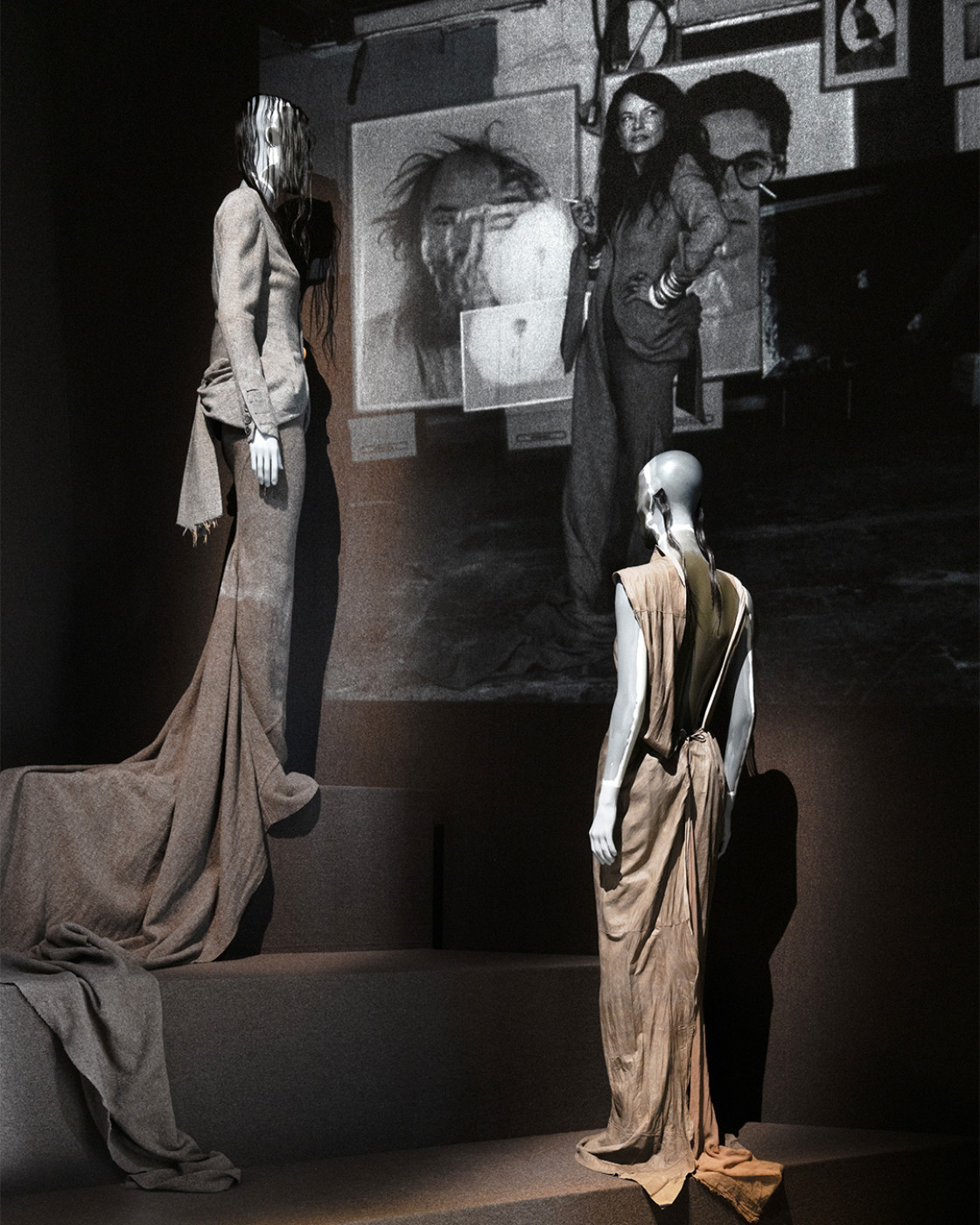

A gothic hymn to beauty, power and personal mythology — Rick Owens has never been one for subtle statements. Now, the avant-garde maestro of Paris Fashion Week receives a suitably theatrical homage: for the first time in its history, Palais Galliera, the city’s pre-eminent fashion museum, is devoting a full-scale exhibition to his radical, unapologetic vision. Titled Temple of Love and on view until 4 January, the exhibition is not just a career retrospective — it’s a spiritual blueprint of the Owens universe. With over 100 silhouettes spanning three decades, newly unearthed artefacts, sculptural furniture and large-scale installations, the show unfolds as both an intimate confession and an architectural performance.

Owens, whose shows dominate the Paris Fashion Week calendar like ritual spectacles — sometimes staged in the brutalist belly of the Palais de Tokyo, other times inside his Place Bourbon headquarters (once home to the French Socialist Party) — is not merely a designer. He’s a system disruptor, a myth-maker, a kind of modern monk for whom the runway is a place of philosophical inquiry. Now, his world spills beyond the catwalk and into the sacred halls of Parisian culture.

The clothes I make are my autobiography. They are the calm elegance I want to get to, and the damage I’ve done on the way,” Owens once wrote, when he started out in fashion in Los Angeles in 1992 — a quote that now greets visitors in the show booklet. “They are an expression of tenderness and raging ego.” Thirty years on, the words still ring true.

Owens personally curated the show alongside Alexandre Samson, Galliera’s rising star of fashion curation in charge of contemporary fashion. Together, they have created something closer to a devotional space than a museum retrospective — an exploration of duality, of discipline and collapse, masculinity and femininity, control and chaos. At Rick, every show is always political, always in defiance of dominant codes. He questions conventional ideas of beauty, taste and belonging — and if the world is in crisis, Owens doesn’t look away. He confronts it. He screams — gently, with love — that there is always another way. His designs, like living sculptures, worn by a devoted gang of recurring models (archetypes of his universe), do more than dazzle: they communicate. You are not alone. There are answers to be found. Because, as Owens says, “showing good-looking clothes isn’t enough anymore.”

“He’s not going to attend a fashion school, but rather a school for industrial pattern-making, a technical school: he’s going to learn fashion not through drawing, but through the very structure of the garment. This is a crucial point in understanding his work — he approaches clothing through its sculptural form. His way of conceiving garments aligns with that of illustrious couturiers like Madame Grès or Monsieur Balenciaga,” explains Alexandre Samson.

Why Galliera? It’s long been one of Owens’ favourite institutions. “Fortuny, a Spaniard in Venice” and “The Treasured Dresses of Elisabeth, Countess Greffulhe” are among the exhibitions he’s returned to for inspiration. His love of Paris runs deep, but it’s this particular museum that has given him the tools — and the trust — to build something deeply personal.

Inside, visitors are treated to fashion as revelation: early silhouettes from his LA years (think underground glamour meets Grecian draping à la Madame Grès), alongside his Parisian-era masterpieces — dystopian, sculptural, defiantly sensual. Materials are reclaimed: army blankets, parachute silk, washed leather. The palette? Monastic: blacks, muted earth tones, and that now-iconic Owens grey, “Dust”.

One soundscape features Owens reading aloud from À Rebours by Joris-Karl Huysmans, a novel of decadent self-isolation and one of his earliest literary touchstones from youth in Porterville, California.

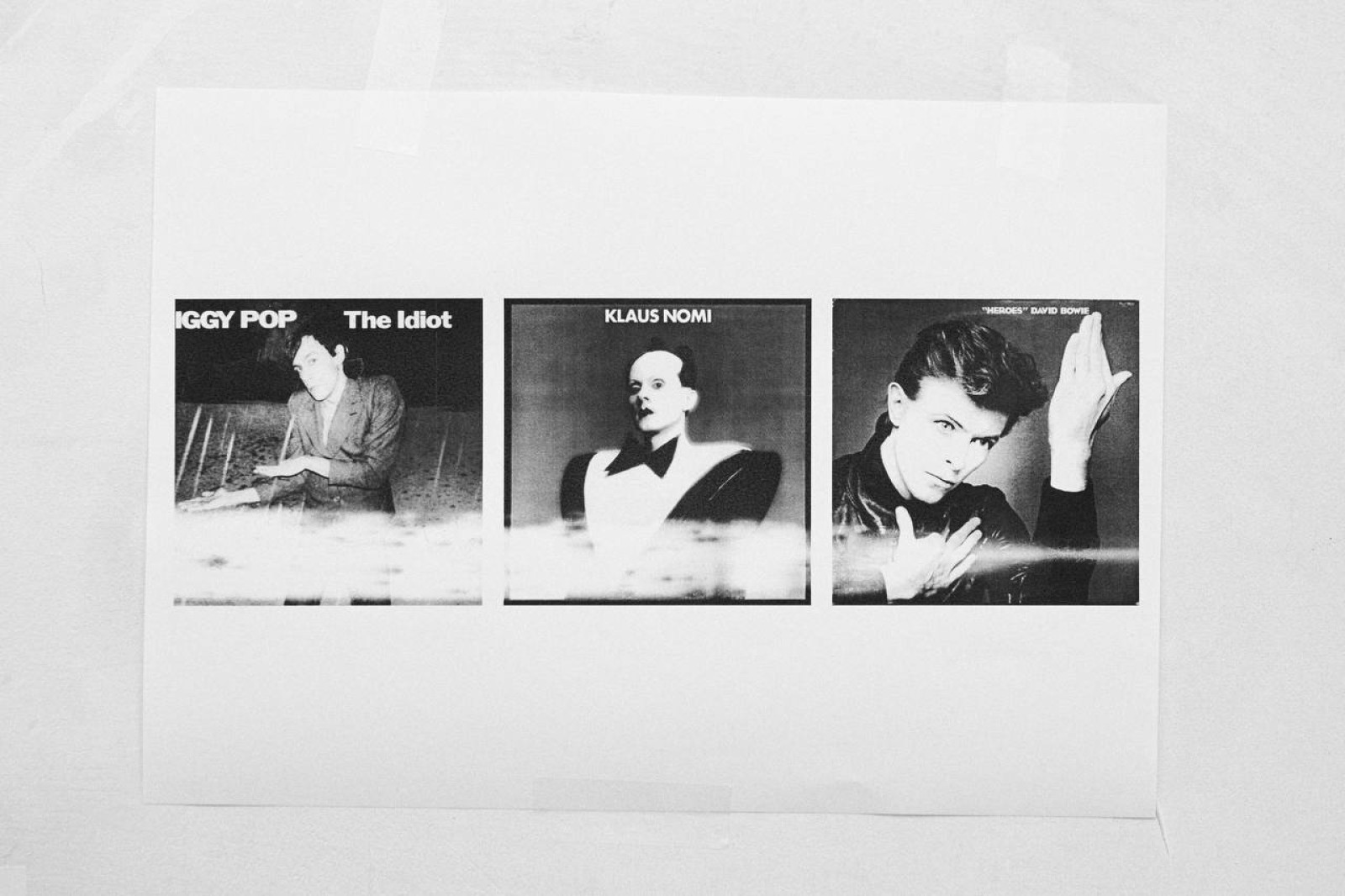

Elsewhere, the layers deepen. Never-before-seen artefacts from Owens’ private archive include the cover of his cherished Ziggy Stardust vinyl — Bowie remains his ultimate fashion deity — and plates created with Michèle Lamy, his wife, muse and eternal co-conspirator, for their cult LA restaurant Les Deux Café. The couple’s former bedroom on Las Palmas Avenue (where they lived from 1994 to 2023) has been meticulously recreated, complete with their beloved book collection — the only possessions they took when they moved to Paris — and their favourite perfumes, featuring bottles from Guerlain and Santa Maria Novella.

Archival pieces from some of his most talked-about early works — including Self Portrait Las Palmas Ave and the evocative Foulard, a meditation on mortality — are displayed alongside his striking life-size fountain sculpture, first presented at Pitti Uomo in 2006. Select early video pieces and conceptual art also hint at Owens’ fascination with unconventional aesthetics. Adding a touch of irony, Owens recently hinted at launching a digital platform dedicated entirely to his feet.

Outside, in a poetic gesture of monumentality, Owens has reimagined the museum’s neoclassical façade. The statues adorning the exterior are wrapped in sequin-embroidered fabric — divine beings refashioned through his lens. The garden, too, has been transformed. With the help of the Ville de Paris gardeners, Owens planted it with Californian vines and blue morning glories, wildflowers from his Porterville childhood. The entire landscape hums with personal memory and myth.

And then there are the 30 brutalist cement sculptures, specially created for the show and scattered like totems across the grounds — part tombstone, part altar, entirely Owens. They are the exhale after the scream; the permanence after the storm.

In a fashion world obsessed with virality and ephemerality, Temple of Love asks us to slow down. This is not just a museum show — it’s a sanctuary. Built of sequins, steel, concrete and soul.

Rick Owens, Temple of Love on view at Palais Galliera, 10 avenue Pierre 1er de Srbie, Paris 16e, until 4 January.

Courtesy: Palais Galliera

Text: Lidia Ageeva