300-year History of HOSOO Reinvents Timeless Heritage

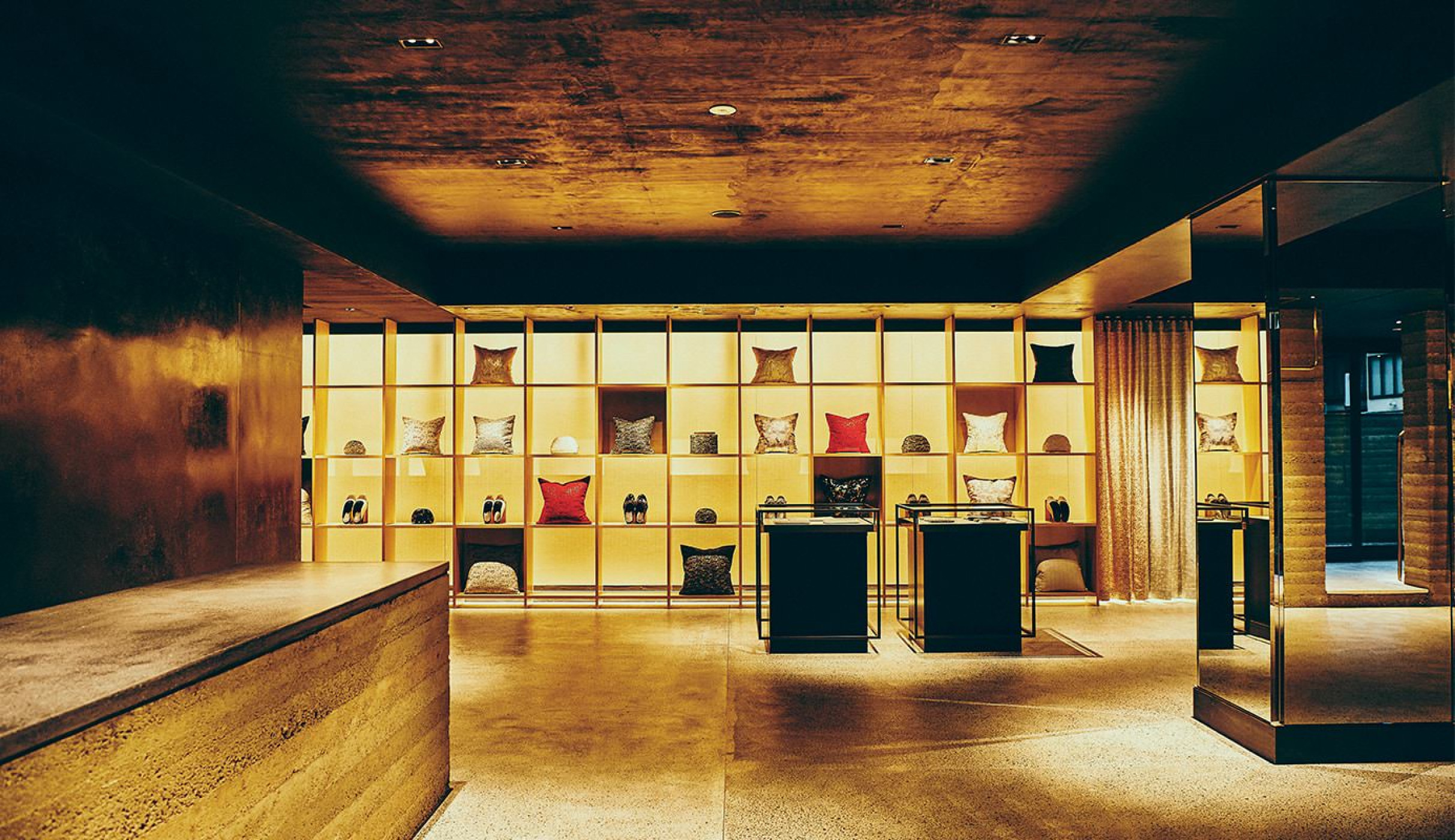

Approximately 1,250 years ago, Kiyomizu Temple was established, and about 400 years ago, the historic Nishiki Market came into existence. These landmarks have made Karasuma, the heart of Kyoto, a thriving tourist destination. This area, home to many historically significant buildings, is also where the flagship store of HOSOO—a fusion of modernity and tradition—stands prominently. Founded in 1688, HOSOO is a venerable Nishijin textile company. In 2019, they established their first flagship store within their headquarters, showcasing their original textile collection.

The store's striking appearance features black plaster walls mixed with charcoal and earthen walls crafted using an ancient Hanchiku technique, creating a four-layer gradient from soil sourced in four locations around Kyoto. This distinctive façade stands out amidst the traditional streetscape and reflects HOSOO's spirit of reinterpreting the essence of craftsmanship from a fresh perspective, all while aiming to connect kimono culture to the future in an era of changing lifestyles and values.

HOSOO's textiles, created using traditional techniques, are utilized in the interiors of luxury brand stores such as Dior, Chanel, Hermès, and Cartier, as well as in five-star hotels like The Ritz-Carlton and Four Seasons. Recognizing the declining Nishijin textile market as a critical issue, HOSOO’s 12th-generation successor, Masataka Hosoo, has emerged as a pioneer who successfully opened international markets, carrying forward a family legacy spanning 337 years.

One of the major factors contributing to the decline of traditional crafts is the lack of successors to carry on the craft. However, thanks to his efforts, applications for Nishijin textile artisanship have surged, with a competitive rate as high as 20 applicants per position. Words like "tradition" and "craftsmanship" often evoke a stiff, formal image, causing young people to shy away. Yet today, a new generation in their 20s and 30s is dedicating themselves to mastering this craft.

The 12th-generation successor himself was once among those hesitant to embrace tradition. "I used to think this was a conservative industry focused on doing the same thing without change, so I had no intention of taking over the family business. I wanted to pursue a more creative field," he recalls. "In my teenage years, I became fascinated by music after listening to the Sex Pistols' Anarchy in the UK. After graduating from university, I joined a major jewelry company while focusing on music activities. Three years in, I heard a talk about 'taking Nishijin textiles overseas' and found it intriguing. I saw new potential in Nishijin textile design, and in 2008, I joined HOSOO.

Looking back now, nothing is as inherently creative as traditional crafts. Nishijin textiles, with a history spanning approximately 1,200 years, are the pinnacle of creativity. I feel it is my role to carry this legacy forward for the next 100, even 200 years."

The art of textile weaving in Kyoto dates back to the 5th century, even before the establishment of Heian-kyo, the last ancient capital of Japan. After the Ōnin War (1467–1477), a conflict that divided the nation, textile artisans who had scattered across the country returned to Kyoto and resumed their craft. It was during this period that the area within a 5-kilometer radius in the northwestern part of Kyoto, which had already prospered as a textile hub before the war, came to be known as "Nishijin."

For a thousand years while Kyoto served as the imperial capital, Nishijin textiles were tailored exclusively for the elite—Emperors, nobles, shoguns, and temples. These exquisite textiles were custom-woven to meet the demands of these high-status clients.

The HOSOO legacy began with its founder, Yahei Hosoo, who started as a Nishijin textile artisan in the 17th century and officially established the company in 1688.

Japan is home to many types of kimono and obi textiles, but why is Nishijin textiles regarded as the pinnacle of quality? The key lies in its unique production process: instead of dyeing the fabric after it is woven, Nishijin textiles uses pre-dyed threads to intricately weave patterns. Unlike conventional weaving, which involves the simple crossing of vertical and horizontal threads, Nishijin textiles employs techniques that combine various types of threads—thick, thin, flat, and more—creating complex, multi-layered structures. This craftsmanship gives the textiles a dynamic quality, with their appearance shifting under different light and movement.

The process is highly labor-intensive, often requiring numerous steps to complete. Centuries ago, artisans could weave only a few millimeters per day, a testament to the meticulous craftsmanship involved in creating these luxurious silk textiles.

"It's akin to cutting a diamond to maximize its brilliance and beauty," he continues. "Historically, textiles served a similar role to jewels for the nobility. Nishijin textiles approximately 20 production steps are not performed in-house but are entrusted to skilled craftsmen, each specializing in their own process. This isn’t about modern efficiency-driven division of labor; it’s a masterclass in pursuing the 'ultimate beauty.'"

A major turning point in the 300-year history of HOSOO came in 1869, when the capital of Japan shifted from Kyoto to Tokyo. "The era of the samurai came to an end, and our primary clients, the imperial family and the shogunate, left Kyoto," he explains. The stagnation that gripped Nishijin was revived by the advent of the Jacquard loom, invented by Frenchman Joseph Jacquard in the 19th century. Previously, complex textiles required both a weaver and an assistant to manage the threads, but Jacquard’s invention enabled a single person to operate the loom.

In 1873, in a bid to master this cutting-edge weaving technology, Kyoto Prefecture dispatched three Nishijin craftsmen to Lyon, France. By successfully adopting and integrating this foreign technology, Nishijin was able to survive and thrive.

"Our materials and techniques sparked innovation and were passed on to the next era," he reflects. "It’s not just about preserving our heritage; it’s about pursuing new beauty and creating textiles that only this era can produce. By incorporating the latest technologies, we continue to explore the textiles of the future. This spirit of Nishijin innovation is something we proudly carry forward."

This innovative mentality transcended time and was exemplified when he joined the family business. It all began when the renowned New York architect Peter Marino emailed him in 2019 after seeing two obi exhibited at the Kansei - Japan Design Exhibition at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris. Marino expressed a desire to use Nishijin textile materials for his store interiors.

Traditional Nishijin fabric is 32 centimeters wide, a dimension derived from the human scale suited to the Japanese body and kimono tradition. However, this width posed challenges for larger-scale products such as chairs or sofas, as seams would be inevitable. This spurred HOSOO to take on an unprecedented challenge: developing a 150-centimeter-wide loom, the new standard for textiles beyond kimono applications.

"What we must do is ensure the techniques we have cultivated are passed down to the next generation. If innovation is the way to achieve that, then we must embrace it," he reflects. Over the course of a year, he worked with craftsmen to develop the new loom and create textiles based on Nishijin techniques and materials. These textiles were used in the walls and chairs of Dior stores across 90 cities designed by Marino, marking a pivotal moment that enabled HOSOO to rapidly expand its textile business.

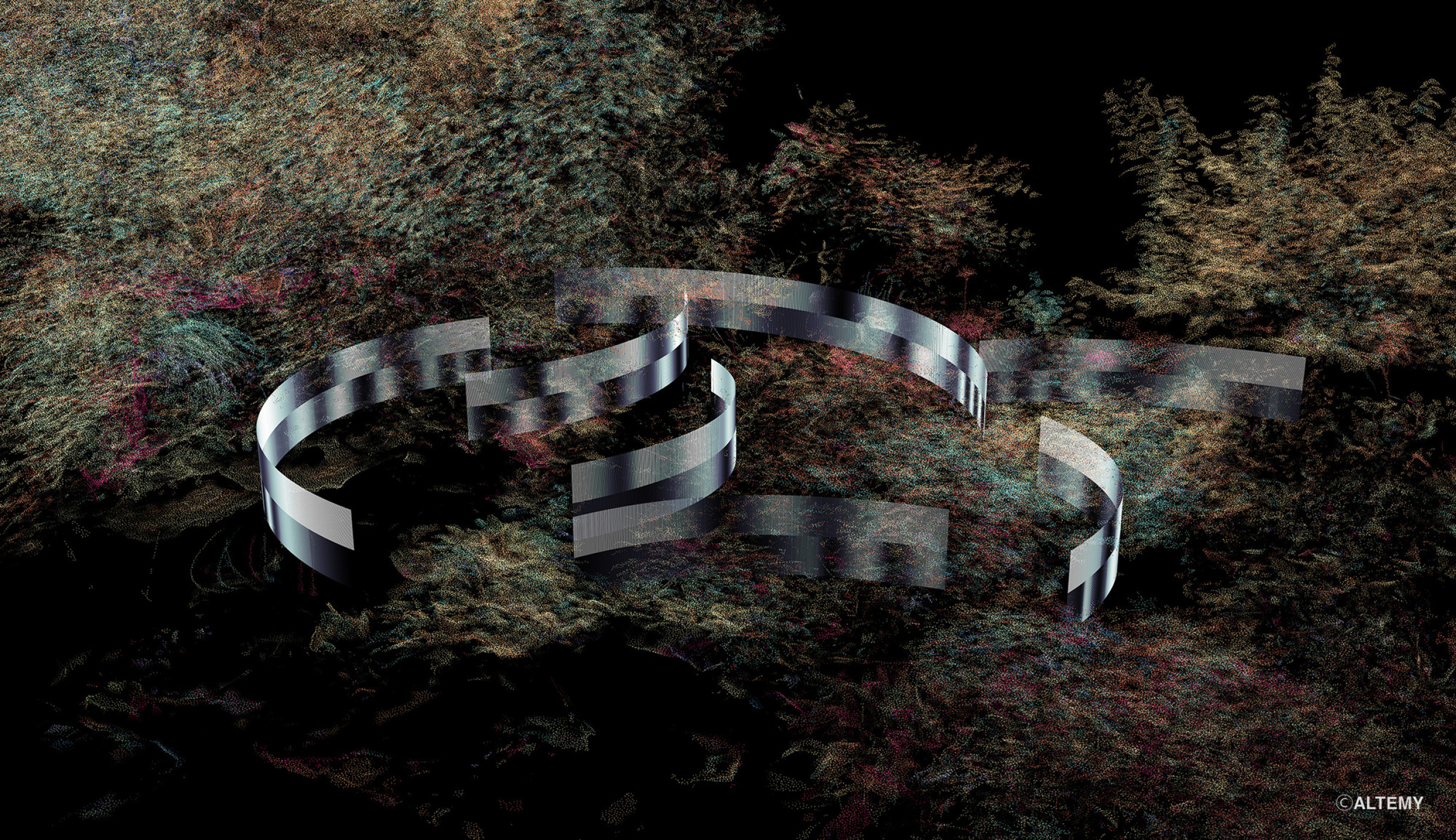

Fifteen years after developing the 150-centimeter-wide loom, in 2025, Hosoo is set to unveil the largest textile in Nishijin's history—an approximately 65-meter-long, 13-meter-high fabric that will cover the exterior of a pavilion at the Osaka Expo. Guided by the motto “More than Textile”, the 12th-generation leader continues to challenge conventional boundaries of textile-making with a bold vision: "It is because I believe in tradition that I am willing to break it in order to keep innovating," he says with enthusiasm.

HOSOO has showcased innovative textiles created in collaboration with university research institutions, contemporary artists, mathematicians, musicians, and engineers at the HOSOO GALLERY on the second floor of their store, as well as at their showroom in Milan. Recently, in partnership with LVMH Métiers d'Art, they exhibited a mobile tea room named “Ori-An,” entirely covered in woven fabric in Paris.

At this year’s Milan Design Week, HOSOO presented a new collection developed in collaboration with AMDL CIRCLE, led by renowned Italian architect and designer Michele De Lucchi. This collection features four motifs blending magnified images of trees with satellite photography, brought to life through the creativity of skilled artisans using natural fibers. The resulting textiles evoke landscapes that can be interpreted as both macro and micro, offering a fresh perspective on the possibilities of weaving.

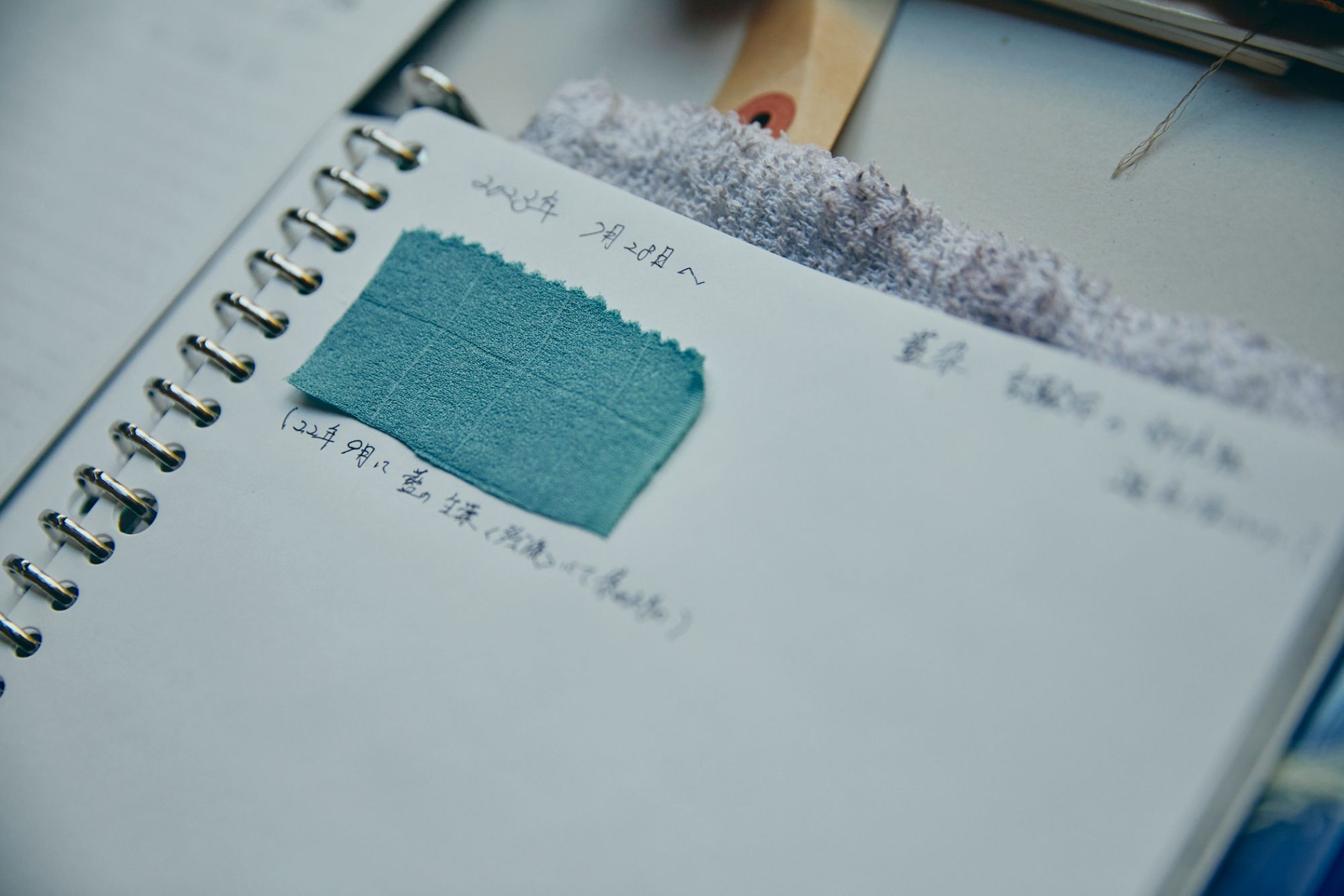

Currently, alongside textile development, Hosoo is deeply invested in natural dyeing techniques. Inspired by the beauty and richness of courtly dyes from the Heian period (794ー1192), he has been conducting extensive research on natural dyeing for years. To revive plants that became endangered with the rise of chemical dyes, HOSOO cultivates them using advanced technology at a dedicated farm in Kyoto's Tamba region. The freshly harvested plants are then dyed at an on-site workshop built on the farm premises.

"There are ultimate recipes left behind by our ancestors over a thousand years ago in their pursuit of beauty, and when we reproduce them today, they yield colors of breathtaking beauty. 'Hints for the future lie in the past,'” Hosoo explains.

He elaborates on the intricacies of natural dyeing: "The colors vary greatly depending on the plant species, the parts used, and the soil they are grown in, which makes the process both complex and fascinating. This is true not only for natural dyeing but also for Japanese craftsmanship as a whole—creating pieces that bring out the unique qualities of the materials and are tailored to each individual client. These creations are then passed down through generations, transcending individual lifetimes. I believe this essence of craftsmanship will play a significant role in redefining 'luxury' in the coming era."

If we were to imagine as far back as 9,000 years ago, when weaving was first born, we might wonder why humans sought "beauty" in such creations. For warmth alone, bark or fur would have sufficed. Why, then, did humans go through the trouble of breaking down plant fibers, spinning them into thread, and developing looms? Why did they devote so much time and effort to decoration? Nishijin weaving, crafted entirely by hand through numerous intricate processes, represents the pinnacle of this pursuit.

"Economic efficiency was secondary; the history of Nishijin weaving is one of striving for ultimate beauty," explains Hosoo. "Through textiles, we want to explore philosophical questions: What does beauty mean to humanity? What does happiness mean to people?"

Beneath the surface of tradition and innovation lies a profound sense of aesthetics, a power to break preconceived notions, and a relentless curiosity that drives innovation. The past, present, and future intertwine there, ensuring that HOSOO's Nishijin textiles will continue to be woven and carried forward.

Courtesy: Hosoo

Text: Elie Inoue